Begin Again

As we begin this year feeling a little more hopeful, it’s worth exploring why this January feels different from those of recent years.

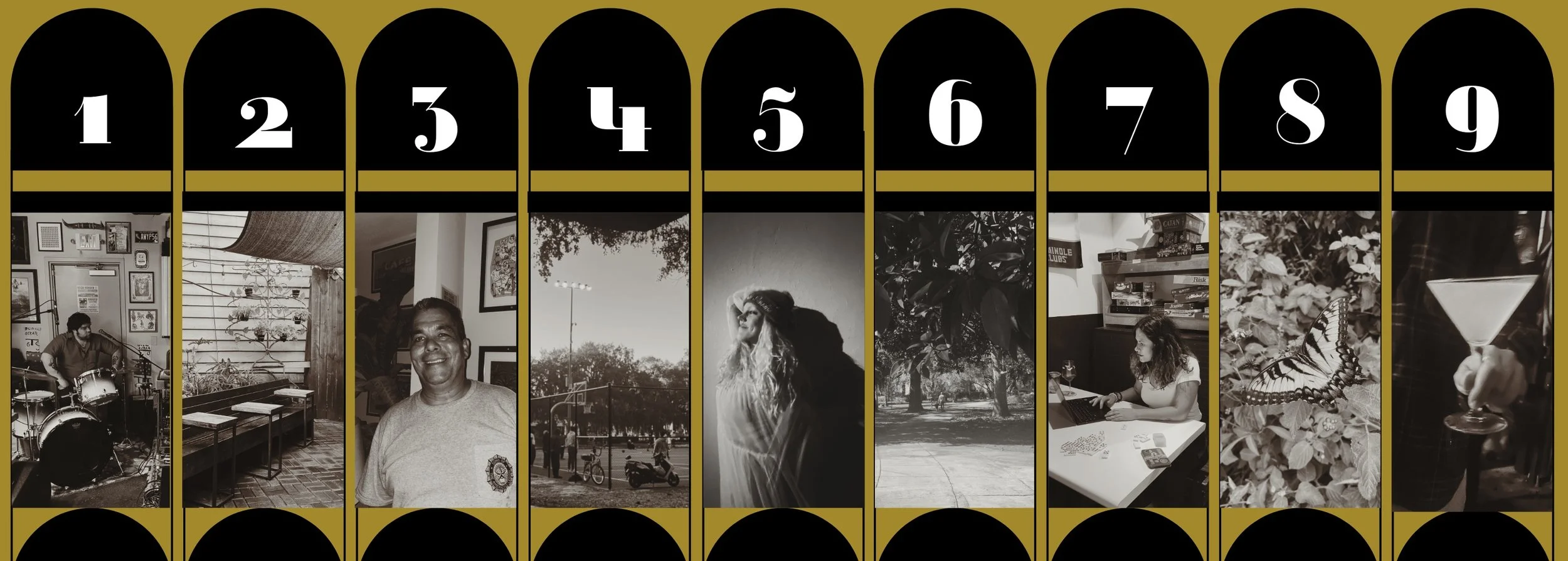

In numerology, the numbers of a year are added together and reduced to a single digit. Each number carries its own energetic themes, moving in a chronological cycle from 1 through 9. 2025 was a nine year, 2026: we’re back at 1.

Reuben Vincent

Reuben Vincent’s Welcome Home isn’t just another release from a promising young MC—it’s the moment he steps fully into the lineage he’s been groomed for since childhood. Blending boom-bap roots, spiritual depth, and the discipline of a true craftsman, Vincent delivers a project that bridges generations of hip-hop lovers while signaling the arrival of an artist built for longevity. Through the mentorship of 9th Wonder, the backing of Roc Nation, and the grounding force of his own emotional intelligence, Vincent proves he’s not simply “next”—he’s actively shaping the future of the genre.

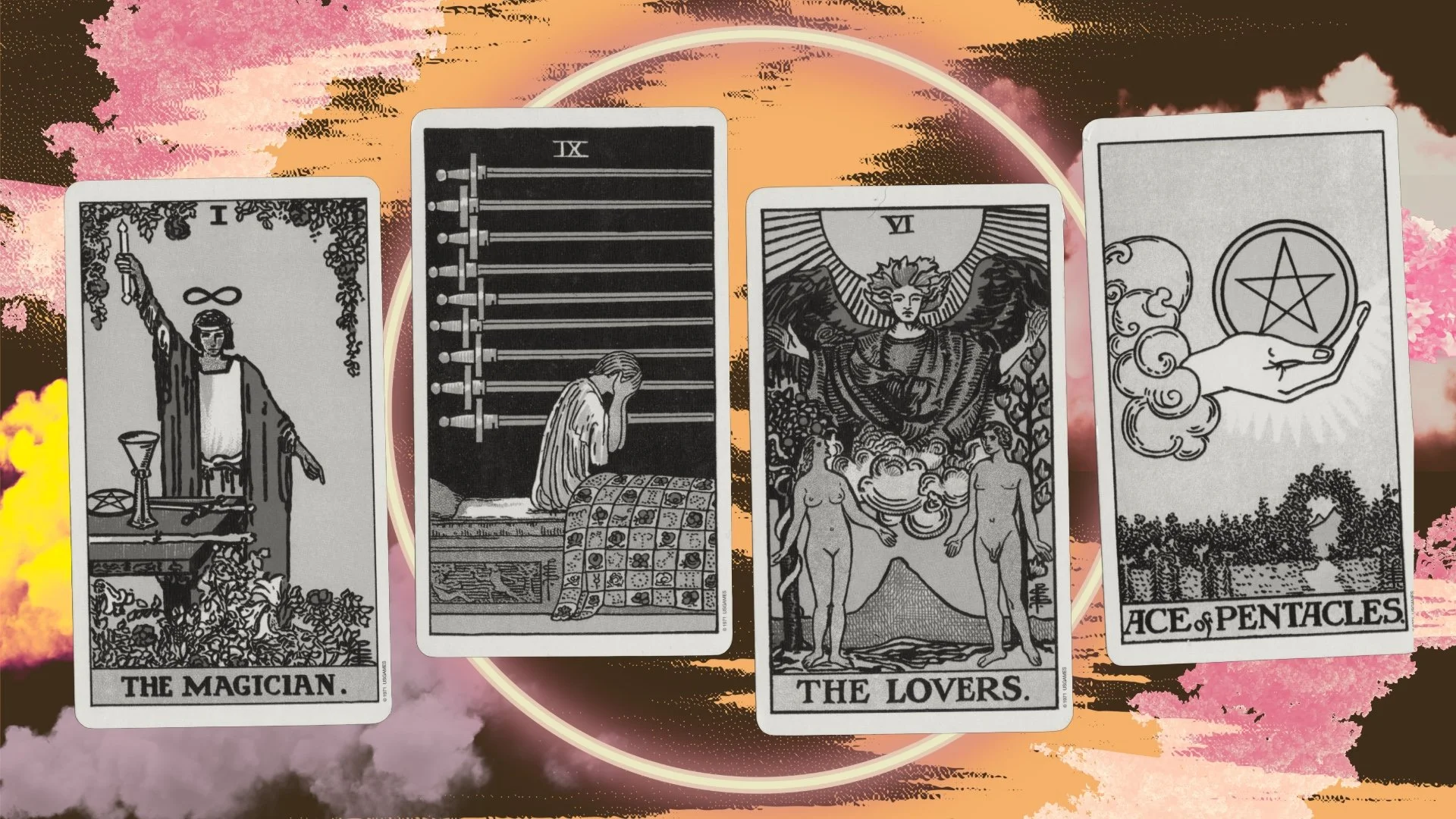

Venus in Scorpio VS Mercury Retrograde

As we move through this Mercury retrograde, this article is your reminder to focus on the good — what you have, what’s God-given, and what you can actually control.

Libras & The In Between

Libras have always shaped society with their fearless hearts. Compassionate and problematic, Libras are one of the hardest signs to pin down. Representing justice and beauty, nobody puts Libra in a corner — simply because they won’t let you.

Exploring Orlando

Orlando long known for its spectacular amusements parks is becoming a food and drink haven. As we explore Orlando and it’s offerings it is only fair we start at Mills Market.

Sour Balls

Mark your calendars: on October 7th, Sour Balls returns to the @thehawthornminibar for another round of boozy brilliance. 🥃🤩

Negroni Week

As you make your weekend plans, here’s a quick look at the history of the Negroni, the philanthropic roots of Negroni Week, and a roundup of our favorite bars participating in this year’s festivities.

New Moon in Virgo

As I begin to share astrology readings here, I want to introduce a perspective that isn’t often emphasized: the idea of treating astrological seasons as harvest times, or dedicated periods of reflection. When you approach the zodiac this way, each sign offers an annual invitation to tend to specific areas of life, ensuring that nothing goes unnoticed in the cycle of the year.

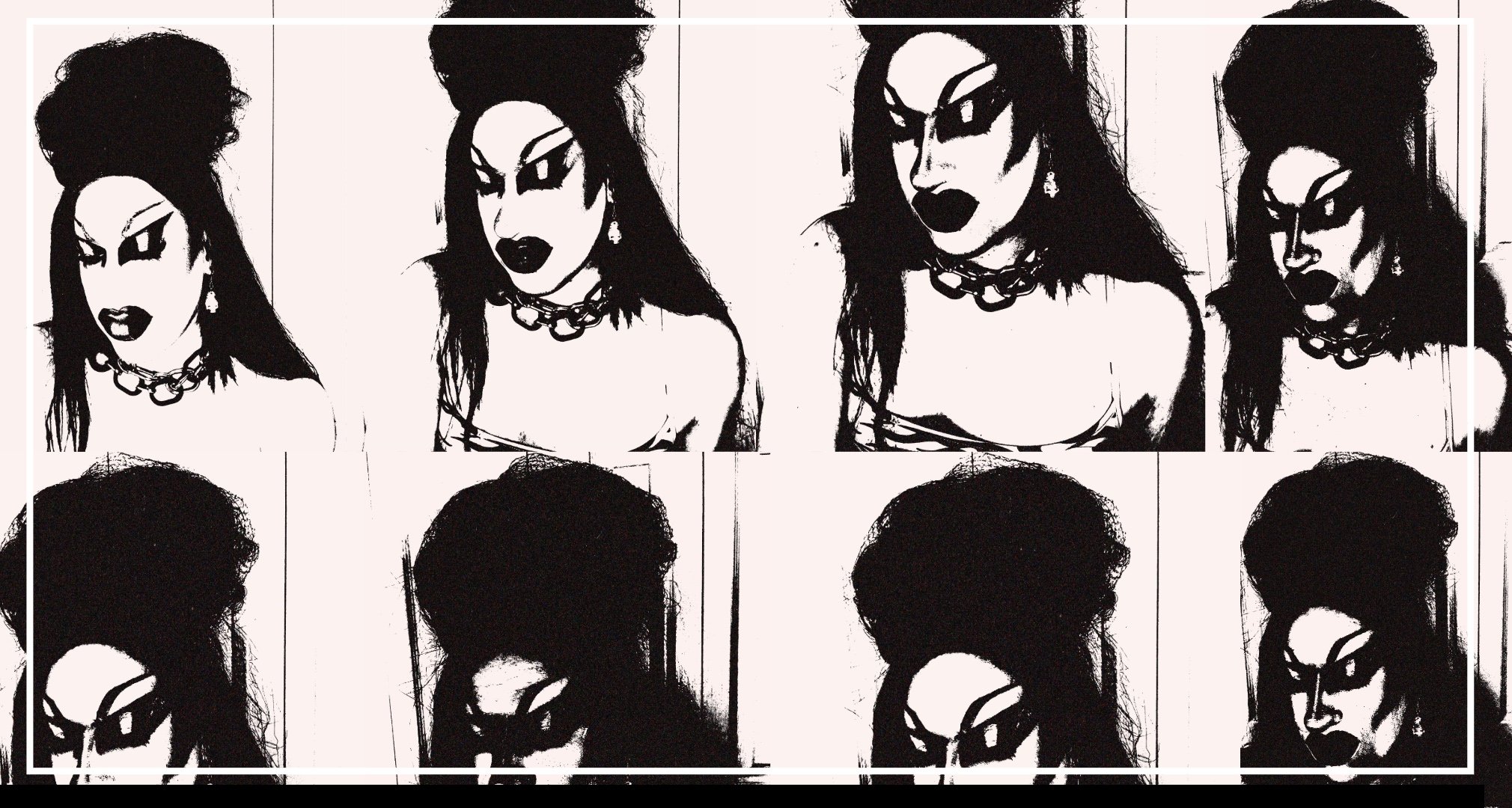

Kylie, You’re A Cutie

As a visionary music producer, vibrant intellectual and drag queen, Kylie gifts the community, queer or not, a modern take on what it means to be in the mix. Uplifting those around her with her contagious kindness, embodying what is, what was, and what will be Kylie Cloud is truly timeless.

Savannah Now

The pulse of community shifts as Savannah continues to evolve. Savannah, The Great Good Place explored the city’s history and framework of community building, but these highlights—left out of that story—are essential stops to ground yourself in Savannah’s spirit, whether you’re just visiting or planting roots.

Kimchi Martini

Since the West Broad Bandshell opened a few months ago, it’s safe to say that everything Chef Romie and Tanika have put out has been extraordinary. This kimchi martini, crafted by bartender Keegan Fleming, nails both concept and sophistication. Whether or not you’re a fan of the brine in a dirty martini, this drink is undeniably sensual. It glides across the palate with a smoothness that balances the sharper notes of gochujang-infused kimchi juice. If Bloody Marys or salinity driven martinis are already in your repertoire—or if you’ve been curious about savory cocktails but never found the right entry point—this is the one.

@20DOLLARS

Sure, Cambridge gets all the love for its fancy schools and buzzing squares, but if you’ve actually been through there, you know it’s the people who make the city what it is. While Gen Z runs from the burbs to this metropolis, copy-pasting whatever they last saw on the internet, this Cambridge icon just does his own thing. Swagger. Brains. Soul. Smoke. Period.

Are You In?

Embodying the spirit of bravery— with an open mind, risks have been taken. The pain that kept us up at night no longer does. Has seeing our beauty and sins in others healed us or make us sicker?

Savannah, The Great Good Place

From Squares to Social Glue: Savannah, a Blueprint for Community-Oriented Urbanism

Through its iconic public squares, lush parks, and gathering spaces, Savannah demonstrates how thoughtful urban design can cultivate lasting human connection and civic life.